Climate finance isn’t reaching Southern Africa’s most vulnerable

The region desperately needs climate adaptation funds but loses out to countries with strong institutional capacity and competitive markets.

Published on 02 November 2021 in

ISS Today

By

Alize le Roux

Senior Researcher, African Futures and Innovation, ISS Pretoria

Despite contributing little to climate change, Southern Africa is among the worst-affected regions globally. And those who are bearing the brunt are the ones with the least resources to adapt.

The region’s governments have not prioritised adaptation measures such as early warning systems, climate-resilient infrastructure, dryland agriculture, mangrove protection, and resilient water sources. And the costs of these measures are rising far faster than funding is being provided. As COP26 kicks off this week, countries in the region must raise funds and increase adaptation planning efforts.

The World Food Programme has called Southern Africa the ‘epitome’ of the link between climate and the water-energy-food nexus. The 16 Southern African Development Community (SADC) states have recorded 36% of all weather-related disasters in Africa in the past four decades. These affected 177 million people, left 2.7 million homeless and inflicted damage in excess of US$14 billion. Climate change will continue to increase the frequency, intensity, duration and locations of these slow- and sudden-onset impacts.

Poor countries have the fewest adaptation resources and the highest costs relative to their economies

Many communities in these countries are poor, with little ability to adapt. Their dependency on natural resources and exposure to repeated and extreme hazards such as floods, droughts, storms and wildfires render them extremely vulnerable.

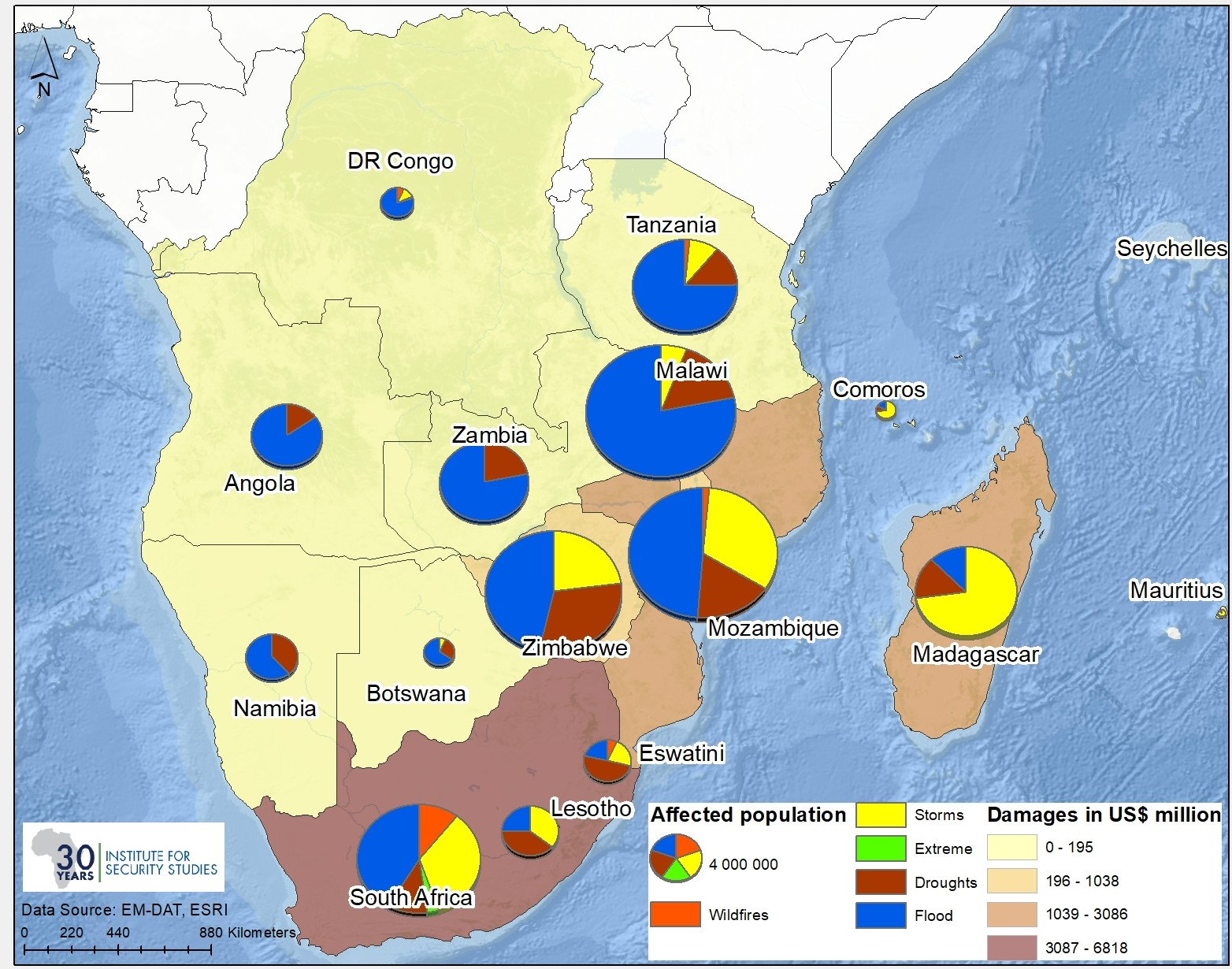

Tropical cyclones and severe thunderstorms tend to be the most destructive in Southern Africa, posing the greatest threat to infrastructure and displacing the most people. Water is the region’s Achilles heel, with 90% of people requiring emergency assistance due to either too much or too little water. Since 1980, there have been 314 floods and 102 droughts in the region (Chart 1).

In total, 606 weather related disasters have been recorded in SADC countries since 1980. Malawi and Mozambique were most affected, with Zimbabwe and South Africa in third and four places respectively. Mauritius, Seychelles and Comoros had the fewest incidents. South Africa, Mozambique, Madagascar and Zimbabwe recorded the largest economic losses while Lesotho, Tanzania and Seychelles recorded the least.

Chart 1: Weather related disasters in Southern Africa, 1980–2020  Source: Authors analyses using data from the EM-DAT Database

Source: Authors analyses using data from the EM-DAT Database(click on the map for the full size image)

As the impacts of climate change worsen, these vulnerable countries will be hit hard. Southern Africa urgently needs adaptation measures, and that means accessing and allocating more funding – a major challenge in itself.

Globally, the least-developed countries have the fewest resources to plan, finance and implement adaptation measures, yet they incur the highest costs relative to their economies. In 2018, Cyclone Ava caused US$156 million in losses to Madagascar, which is 2.9% of the country’s 2017 gross domestic product (GDP). In 2019, Cyclone Idai cost Zimbabwe US$274 million and Mozambique US$3 billion, 1.6% and 19.6% of their respective GDPs that year.

Climate funding is unequally distributed worldwide. Africa received only 26% of available financing between 2016 and 2019. Three-quarters of that was in the form of loans and other non-grant instruments that must be repaid. Most has been directed towards cutting emissions (mitigation), with adaptation assigned only 21% of global climate funding in 2018.

South Africa received the most climate financing in Africa, but only 2% is directed to adaptation

South Africa received the most multilateral climate financing on the continent and is placed sixth highest internationally. But only 2% is directed to adaptation, with the rest going to mitigation (Chart 2). Zambia, Tanzania and Comoros received relatively high amounts of adaptation financing relative to their climate vulnerabilities, yet the sums are still inadequate to meet their needs. Botswana received no adaptation financing.

Chart 2: Number of people affected vs total climate finance and adaptation funding in Southern Africa  Source: Authors analyses using data from the Climate Funds Update and EM-DAT Database Source: Authors analyses using data from the Climate Funds Update and EM-DAT Database( (click on the graph for the full size image)

|

While climate financiers regularly speak about prioritising the most vulnerable countries, vulnerability is not a key factor in determining where funds go. Germanwatch’s Global Climate Risk Index 2021 ranked Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Malawi the 1st, 2nd and 5th most affected countries in the world in 2019. Yet, they placed 32nd, 108th and 75th in climate financing received.

Many countries with the highest risks are left behind. Finance tends to flow to places where donors have a presence and to countries with strong institutional capacity to implement projects. Investors seek predictable environments to generate returns and are reluctant to invest in countries with poor institutional and market settings and records of corruption.

In Zimbabwe for example, awareness has grown and climate change is becoming a government priority. Yet policy and adaptation planning are still in their infancy, and Zimbabwe hasn’t been able to attract desperately needed funding. The government and multilateral funding bodies view adaptation differently, and the disharmony between the public and private sectors does not inspire confidence.

When vulnerable countries receive adaptation finance, it doesn’t always reach the communities most at risk. Adaptation funding is typically driven internationally and directed nationally with little input from the local level, where expertise is often lacking. For instance, over 70% of respondents in a study of people displaced by Cyclone Idai didn’t know about climate change or adaptation. And in many cases, funds are lost to corruption long before they reach their beneficiaries.

Adaptation funding is driven internationally and directed nationally with little local level input

Despite these challenges, climate adaptation is progressing. As of 2021, 72% of all countries have at least one national adaptation planning instrument. All Southern African states except Angola and Botswana have adopted national plans and Botswana has launched an adaptation framework.

Some donor countries have begun developing ‘green taxonomies’ to help identify investments that contribute to mitigating or adapting to climate impacts. More innovative models and more grant instruments are needed to increase the quantity and quality of adaptation financing and projects. Early action is imperative as costs increase rapidly over time.

Southern African countries should be focused on mobilising adaptation funding at COP26. They need to mainstream climate adaptation into policies and projects across all sectors so that adaptation planning becomes the norm and the need for funds decreases over time. The economic, social and environmental costs of not adapting are enormous.

Aimée-Noël Mbiyozo, Senior Research Consultant, Migration and Alize le Roux, Senior Researcher, African Futures and Innovation, ISS Pretoria

Exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles have been given to Daily Maverick in South Africa and Premium Times in Nigeria. For media based outside South Africa and Nigeria that want to re-publish articles, or for queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.

Photo: World Vision