Overfishing forces Zambia’s third Lake Tanganyika fishing ban

Once-abundant fish stocks must be replenished, but the ban alone won’t inspire more sustainable lake use by local communities.

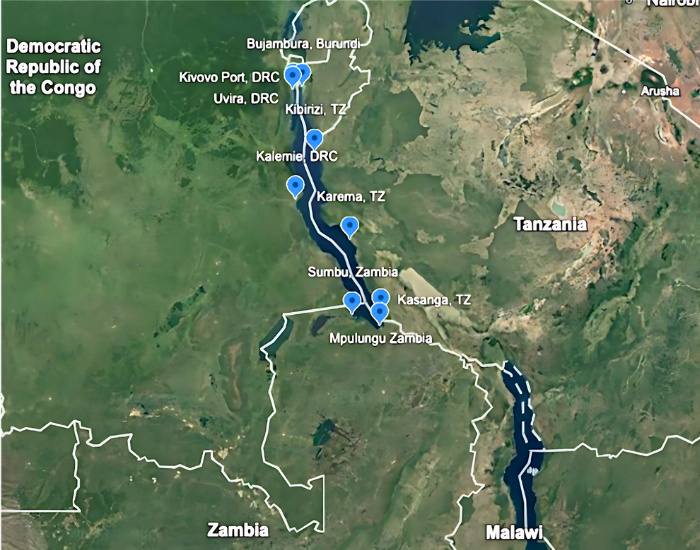

Lake Tanganyika is Africa’s longest and deepest lake, with a shoreline lengthier than Tanzania’s entire coastline. It supports local livelihoods and the economies of riparian countries through its rich biodiversity and central role in regional trade and transport. However, unsustainable activities like overfishing threaten the lake’s resources.

Lake Tanganyika’s waters are shared by Tanzania (41%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (45%), Burundi (8%), and Zambia (6%). The lake is governed by the Convention on the Sustainable Management of Lake Tanganyika, which established the Lake Tanganyika Authority (LTA) to facilitate integrated management between the riparian states.

The lake’s growing population, around 12.5 million in 2012, is predicted to rise by at least 2% annually. This increases demands on the lake, which already suffers due to climate change, overexploitation, harmful land use practices and pollution.

|

Key ports in Lake Tanganyika

Source: Google Earth

|

Its aquatic ecosystems are among the most biodiverse globally. Hundreds of its fish species are endemic to the lake, and fishing is the primary livelihood for shoreline communities. The Lake Tanganyika perch (Lates stappersi), locally called buka-buka, and two sardine species (Limnothrissa miodon and Stolothrissa tanganicae) or kapenta, form the bulk of Zambia’s Lake Tanganyika fisheries.

Most catches are destined for surrounding communities, the Copperbelt, Lusaka and DRC. There is also limited recreational and sport fishing, and a niche market for ornamental fish for aquariums, especially Lake Tanganyika’s endemic cichlid species.

While industrial fishing was previously the primary fisheries sector in Zambia’s portion of the lake, semi-industrial or artisanal fishers gradually overtook the market share. Today, most fishing is by semi-industrial and subsistence fishers.

Semi-industrial fishers began catching more species, using more vessels, larger groups of fishers and more effective methods. This, compounded with other impacts like climate change, has reduced stocks. A fisher told the Institute for Security Studies, ‘Where you used to catch 50 pieces, now it is three pieces, four pieces.

State assistance has been minimal during the ban, which can be devastating for those without alternative livelihoods

As catches declined, fishers increasingly turned to illegal methods to increase their yield, including using prohibited monofilament and drift nets that capture juvenile and undersized fish. Monofilament nets are reportedly imported in bulk from China, often passing through Tanzania, where they are also prohibited. A Nsumbu-based conservation organisation reported a single seizure of monofilament nets worth US$180 000 in 2024.

Divers also collect endemic ornamental fish species for the global aquarium trade. Although cichlids are prized, eels and other species like catfish, are also targeted.

Zambia’s fisheries department reported issuing only two ornamental fishing licences to local companies in 2025. However, sources say there are many more illegal divers, including in Nsumbu National Park, which borders the lake in northern Zambia. Fish are transported to Lusaka or Dar Es Salaam, from where they are flown to Europe, the United States, Asia and South Africa.

Because their cross-border trade is not regulated by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), establishing illegality once shipments leave Zambia is difficult.

Zambia’s Fisheries Act prohibits fishing without a licence, limits fishing effort and prohibits certain methods and gear, but doesn’t provide for quotas. In 2023, the stock decline saw the LTA implement an annual fishing ban. While all four riparian countries should implement the ban, only Zambia has diligently enforced it annually.

Fisheries officers from Mpulungu, home to Zambia’s only international port, say most fisherfolk adhere to the ban because they have seen their catches increase following previous bans. Tanzania, the only other country to have implemented the ban, has experienced the same. But ‘where there are rules, there are also rule breakers,’ officers say.

Steps taken by Zambia could provide a blueprint for the DRC, Burundi and Tanzania to implement the ban

Despite Zambia overseeing the smallest section of Lake Tanganyika, its monitoring, control and surveillance abilities are restricted by limited resources, including patrol boats and insufficient staff. Although new technologies are being piloted in other Zambian waterbodies, the fisheries department lacks vessel monitoring technologies or drones to expand its reach across the lake.

Enforcement challenges are not limited to the lake. Without official fishing ports, fish are landed along the shoreline, often directly at informal markets, where they are sold. Fisheries officers cannot monitor all landings, limiting catch data needed for fisheries management decisions.

To complement their operations, the fisheries department often combines efforts with counterparts like the police and special forces marine commandos. They also rely on community policing through fisheries co-management with village conservation development committees.

Yet, the fisheries department’s relationship with communities is complex. Low literacy reduces locals’ understanding of regulations, exacerbated by the absence of an independent monitoring, control and surveillance unit. Fisheries officers act as both fisheries officials and compliance officers – gathering catch data one day, and burning the same fishers’ illegal nets the next.

Community members therefore hesitate to share information with the department. Their trust is further undermined when they receive no response to reports of infringements, due to limited state resources or corrupt officers.

|

Confiscated fishing nets lie outside the Mpulungu police station

Source: Author

|

Dried fish is sold at Ngwenya market in Mpulungu, Zambia

Source: Author

|

Government assistance to communities has been minimal during the ban, which can be devastating for those without alternative livelihoods. As a result, many oppose the ban.

Fisheries are also used as a political weapon. Sources say fishing regulations are used to garner votes, often destroying well-established practices and structures that must be rebuilt post-elections. This includes village conservation development committees.

While there is cross-border cooperation to gather fisheries data to inform lake-wide management, the ban’s unbalanced implementation shows that cross-border resource governance is fragmented. The LTA was established to address this, but riparian states’ limited capacity cripples counter-efforts. To boost national capacities, the LTA has partnered with the European Union and United Nations to implement projects aimed at conserving biodiversity and sustainable use.

These efforts are encouraging, and Zambia’s commitment to the annual fishing ban is commendable. But these actions alone won’t inspire sustainable lake use. Integrated resource management by the riparian countries is needed, without over-reliance on external funding.

Investment in alternative livelihoods beyond the lake’s biodiversity should be explored. Key ports like Mpulungu could be expanded to facilitate trade, and more aquaculture could relieve pressure on wild fish populations. Additional fish centres could also be developed to preserve and process catches. A wider range of government departments will have to contribute to such holistic reforms.

National monitoring, control and surveillance capacity should be bolstered using increasingly affordable technology. Imposing quotas or closed fishing seasons in selected sites could regulate fishing year-round, provided they can be enforced and fisherfolk are sensitised to their sustainable use benefits. Sustainable use can also be encouraged by providing affordable legal fishing gear and preventing prohibited gear from entering Zambia.

If achieved, these steps could provide a blueprint for the DRC, Burundi and Tanzania to also implement the ban.

Exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles have been given to Daily Maverick in South Africa and Premium Times in Nigeria. For media based outside South Africa and Nigeria that want to re-publish articles, or for queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.