Funding shortfall threatens African Union Commission restructuring

Improved member state contributions and investments could hold the key to reinvigorating the AU Commission.

Heads of state, at the 11th extraordinary summit of the African Union (AU) Assembly on 17 and 18 November 2018, entrusted the AU Commission (AUC) with proposing a ‘streamlined and detailed’ departmental structure. This would be part of the AU institutional reform initiated in 2017 and would replace the 2003 Maputo structure, which was considered too large, cost-ineffective and operationally inefficient. Under the auspices of the Rapporteur Group of 10, the AUC recommended reducing its departments from eight to six. The AU Executive Council considered this at its 35th meeting in Niamey, Niger, on 27 and 28 June 2019, and it was adopted by the AU Assembly in 2020.

The restructuring of the AUC was based on AU institutional reform objective four: ‘Manage the African Union’s workings effectively and efficiently at the political and operational levels.’ A successful restructuring would result in a more efficient AUC, capable of driving the AU’s transformation into a stronger entity. To roll out the plan, the council (EX.CL/Dec.1073(XXXVI) instructed the AUC to remain strictly within resources available from the AU budget and partners’ funds to avoid extra costs for member states.

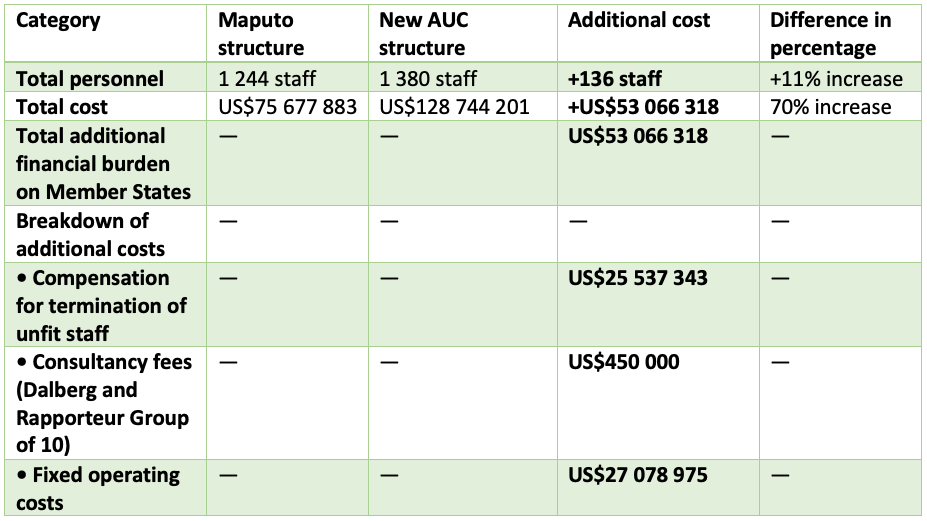

However, the latest Skills Audit and Competency Assessment (SACA) special audit report ― issued in January 2024 ― noted the new structure’s supplementary costs were70% higher than funding for the Maputo institutional composition. The report indicated that delays in implementing the AUC’s new structure ― in assessed staff placement, compensation for unfit staff termination and recruitment ― were due mainly to member states’ struggles to cover the financial gap.

The new AUC structure’s extra costs are 70% greater than funding for the Maputo institutional arrangement

Nevertheless, the council, during the AU and regional economic communities (RECs) mid-year coordination meeting in July 2025, reiterated adherence to the initial decision to not exceed resources. The AUC was instructed to proceed with placements and terminations and with recruitment to fill vacancies across departments.

Financial implication

While the Maputo structure comprised 1 244 staff and cost US$75 677 883, the new structure amounts to US$128 744 201 for 1 380 personnel according to the SACA 2024 audit report. This translates to a US$53 066 318 supplementary financial burden and an additional staffing need, to be covered primarily by member states.

|

New AUC structure cost implications

Source: January 2024 SACA special audit report

|

Although 49% of the supplementary amount covers one-off payments such as service terminations and consultant fees, US$27 078 975, or 51% of US$53 066 318, is to be allocated every year by member states. According to members of the AU Permanent Representatives Committee (PRC) and the SACA steering committee, the long-term burden would be consequential for states amid growing domestic socioeconomic struggles and shifts in donor interests.

A 10-year projection by an AU senior finance officer — interviewed by the Peace and Security Council (PSC) Report — indicates a cumulated fixed operating cost of US$270 789 750, which could exacerbate members’ financial burden. However, the challenges stem from states’ irregular and capped contributions to the AU budget, despite the 2015 Johannesburg plan promoting states’ 100% cost coverage of the AU-assessed budget.

As of January 2024, non- and partially contributing member states were US$84 719 488 in arrears, which the AU finance department is trying to recover ― although without a clear strategy according to SACA auditors. Moreover, as the auditors indicate, since 2020, the AU Assembly has maintained a capped contribution to the AU budget of US$250 000, shared among states, which contrasts with the ongoing ambitious reform process, including the AUC restructure.

More efforts needed

Members’ reluctance to invest more resources in AUC restructure is understandable, given their stretched domestic and continental/global commitments. However, the success of the process requires adequate and predictable funding for two reasons.

To achieve Agenda 2063 and position itself globally, the AUC must build in-house capacity

The first is the growing AU positioning in multilateralism and the numerous internal issues that the AUC, particularly, must address across its five regions. These require the ability to drive African initiatives and manage multilateral partnerships, implementing and following up on decisions of heads of state, the PSC and other AU key organs. The decision to proceed with placements and additional recruitment should, therefore, be re-examined.

A PSC Report discussion with an AU senior leader revealed that member state commitment to fund staffing across several departments since 2023 could not be fulfilled. Staffing at the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, was to be covered 75% by member states, yet they’ve covered their commitment at only 35% to date, leaving a 65% deficit.

This case, according to other AU interviewees, demonstrates funding struggles stemming from accumulated arrears and declining state contributions. This is compounded by the current shift in donors’ priorities, which has been noticeable since early 2025.

Secondly, in the prevailing labour environment, the AUC needs to offer competitive wages, benefits and growth plans to attract and retain the best talent. To achieve its core Agenda 2063 projects and position itself globally, the organisation should build in-house operational capacity. Saving costs at the expense of this would be a missed opportunity.

Funding possibilities

Member states should be reminded of the rationale for the AUC restructure ― to strengthen implementation and delivery capacity. While managing continental affairs should be cost-effective, savings should be aligned with operational needs. Member states’ strict adherence to cost limitation seems to overlook operational realities. The council and member states should consider SACA recommendations for a reassessment of staffing needs and financial implications.

An Endowment Fund could improve AU’s capacity to fund the new structure’s annual US$27 million operating cost

The AUC, specifically its finance department, must recover arrears from member states and implement the 0.2% import levy to fill the financing gap. It should explore funding alternatives, maybe following the AU Peace Fund’s diversified resource mobilisation model, attracting contributions from member states and the private sector.

Similarly, part of the mobilised resources could be endowed to generate a profit, which could replenish the budget and enhance medium- and long-term financial capacity. With more than US$400 million, the AU Peace Fund has generated considerable profits, US$19 million of which was disbursed to sustain peace efforts between 2023 and 2024. Extending this resource generation approach to the AU’s assessed budget management, even partially, could provide a considerable share of the US$27 078 975 fixed operating yearly cost of the new structure.