Will AU efforts in 2023 be business as usual?

Enduring and emerging peace and security issues will keep Africa’s authorities on their toes.

In 2022, a complex admixture of external and internal threats coalesced to undermine Africa’s peace and security, and tested the resilience and efficacy of regional and continental response mechanisms. Policy actors grappled simultaneously with widescale, interconnected regional challenges, and with major external shocks from the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Despite this, the AU played a key role in the Ethiopian cessation of hostilities agreement and the Sudan peace deal. However, backsliding remains a risk.

Flashpoints in 2022

Four trends shaped African peace and security in 2022. First, regionalised conflicts persisted, which manifested in dynamics around armed conflicts in Ethiopia, South Sudan, the Central African Republic (CAR) and the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Second was deepening, expanding violent extremism, which increasingly threatened certain African states. In the Sahel, jihadists expanded their activities to coastal states, including Benin, Côte d'Ivoire and Togo. In the Horn of Africa, al-Shabaab remained a potent threat across significant parts of Somalia. Repeated attacks by Boko Haram splinter groups wreaked havoc in Lake Chad Basin. And armed attacks by Islamists on military outposts, civilians and infrastructure surged in Mozambique’s northern province of Cabo Delgado.

Unconstitutional changes of governments (UCGs) continued, with two successful coups in Burkina Faso and three failed attempts in Guinea Bissau, The Gambia and São Tomé and Principe. This followed attempted and successful coups in Chad, Mali, Guinea, Sudan and Niger in 2021, which exposed African governments’ weak problem-solving capacity.

The AU played a vital role in the Ethiopian and Sudanese peace deals but backsliding remains a risk

Fourthly, in Sudan, CAR, Chad, Burkina Faso and Libya, political transitions became more protracted in 2022, with the timelines for implementation of peace agreements delayed in South Sudan. The knock-on effects of factors such as COVID-19 and the Russian-Ukrainian war ― namely inflation, worsening food and energy security, and a weakened multilateral system ― added to the complexity. As these factors are not expected to improve markedly in 2023, what will the AU need to prioritise?

Recent successes

In managing the dynamics, the AU stepped up conflict management and democratic consolidation efforts, achieving relative success in diplomacy, peace support operations (PSOs) and review of normative governance frameworks. Progress included an agreement to end hostilities in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region and one that paves the way for the establishment of a civilian government in Sudan. These reflect the potential of AU mediation to advance peace, security and stability on the continent.

The AU’s preventive diplomacy role was evident in the elections and peaceful power transfers in Kenya and Lesotho. Its continued commitment to restoring lasting peace, security and stability in Somalia showed itself in the successful evolution of the AU Mission in Somalia into the AU Transition Mission in Somalia. Another achievement was its support for the implementation of the Southern African Development Community Mission in Mozambique mandate.

Failure to discuss ‘sensitive’ situations questions the AU’s values on collective security

In addition, AU commitment to promoting democracy and good governance was clear in the adoption of the Accra, Malabo and Tangier declarations. These declarations illustrate progress in addressing UCGs and their repercussions for democratic consolidation, peace and security. Other key engagements seek solutions to country- and region-specific conflicts via different mechanisms, missions and representatives.

Familiar issues in 2023

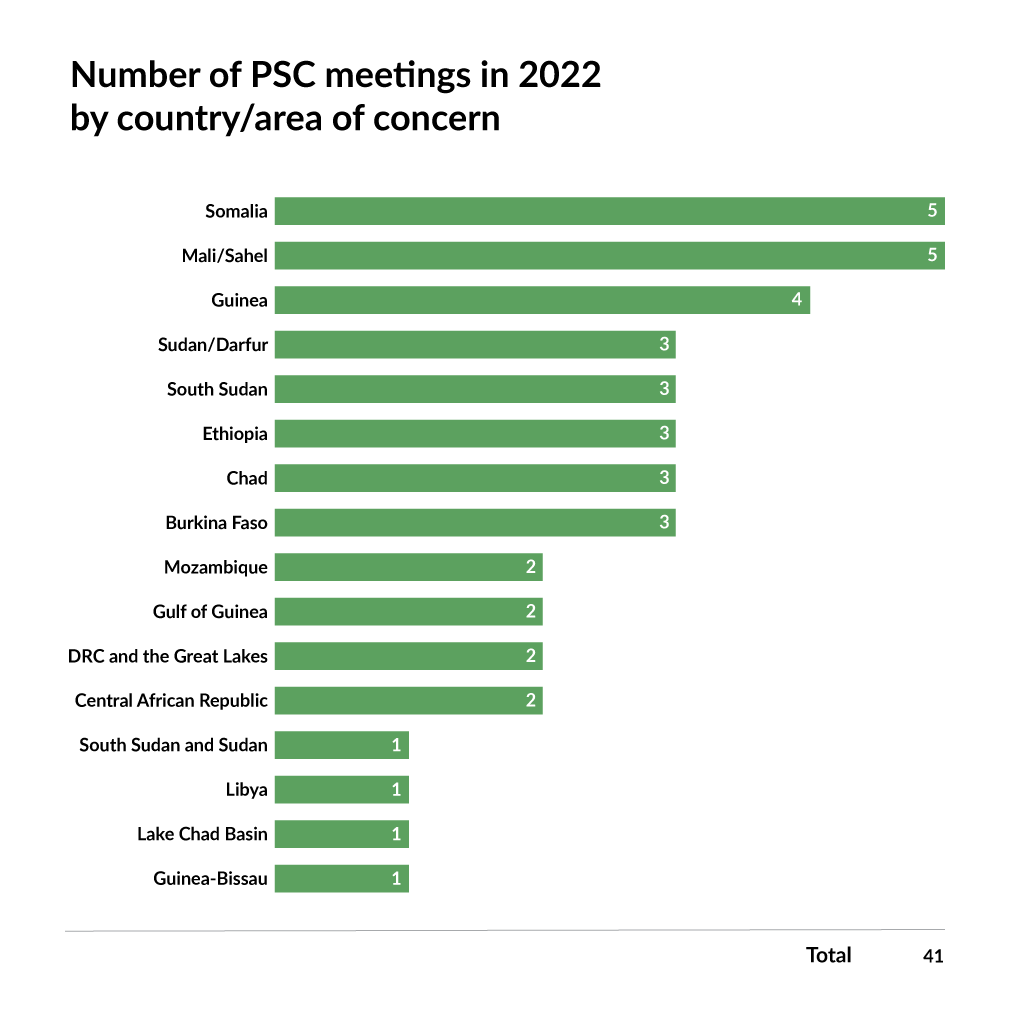

In 2022, the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) met 41 times to discuss conflicts and transitions. Most deliberations focused on Somalia, Mali/the Sahel, Guinea, Sudan/Darfur, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Chad and Burkina Faso. Despite limited progress, none of these cases has been completely resolved and all will need greater attention in 2023.

(click on the graph for the full size image) |

Therefore, management of ongoing peace processes will feature regularly at PSC sessions, with crises driving instability and violence in the Sahel, eastern DRC and Cabo Delgado expected to be prioritised. To build on the progress of 2022, the AU needs a more refined conflict-resolution approach focusing on the structural drivers of these situations.

The AU also plans to accompany the return to constitutional order in Sudan and Chad, where complexities are delaying transition, heightening the risk of military takeovers and protracted civil unrest. South Sudan, Libya and CAR, with their slow peace agreement implementation, will require attention too.

In addition, the PSC agenda will include fighting violent extremism and its linkages with organised crime in northern Mozambique, Somalia, the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin regions. The AU will need to secure sustained financing for PSOs amid shrinking European Union support, while expediting implementation of continental mechanisms to combat terrorism.

With 15 countries set to hold presidential, parliamentary and local elections in the remaining months of 2023, scaling up efforts to consolidate electoral democracy will be a PSC priority. Existing recommendations from AU observer missions will need to be enacted, as will preventive diplomacy, early warning engagements and support for the work of the Panel of the Wise.

In search of greater impact

Enhancing effectiveness in AU peace and security interventions in 2023 will take Africa closer to silencing the guns by 2030, advancing the continent towards a fundamental Agenda 2063 aspiration. For the AU to address effectively and impactfully peace and security challenges this year, it must tackle operational bottlenecks, ensure uniformity in the application of principles and emphasise greater inclusivity.

Resolving conflicts requires a paradigm shift in how sovereignty and subsidiarity are applied

Dynamics that have steered the PSC away from discussing sensitive issues through lack of political will and constrained capacity will continue to frustrate AU efforts. This was a major weakness of the organisation’s engagements last year. The unwillingness of PSC members to be featured on the agenda led to the council’s lack of robust debate on issues affecting Tunisia, Mozambique and Cameroon, among others.

Failure to discuss ‘sensitive’ situations questions how much value the AU places on collective security, which is central to regional and continental efforts to achieve peace and stability. To fulfil its commitment to the African people, the council must find ways to manage country sensitivities.

Sovereignty and subsidiarity are key to AU functions. However, their selective use by some member states has affected the council’s ability to prevent or respond to peace and security crises. In Sudan and Ethiopia, efforts were limited in part due to sovereignty. Subsidiarity issues between the council and regional economic communities (RECs) complicated the former’s oversight role in situations such as UCGs in West Africa and response to the Mozambique crisis.

To improve the council’s impact in 2023, member states must seriously consider their use of these concepts to centre REC and AU roles in collective security and the responsibility to protect. Finding common ground in dealing with existing and emerging conflicts will require a paradigm shift in conceptualisation and application of sovereignty and subsidiarity.

Although not feasible in the short term, this demands commitment by continental leadership to the social contract across member states. In addition, the AU Commission and influential PSC members should discuss the principles during their sessions to reach consensus on their application.

Finally, prospects for resolving peace and security challenges in 2023 will be complicated by a lack of capacity and political will to act decisively. Where will exists, the capacity to act is wanting. To achieve impact in 2023, the AU must act decisively within its powers while securing capacity and resources to sustain efforts.

Prioritising partnerships in response to evolving threats will be crucial. The PSC will need to strengthen its engagement with RECs and the A3 at the UN Security Council, while working to enhance its partnership framework.