More questions than answers in South Africa’s latest victim survey?

Despite some limitations, the survey complements official crime statistics which are compromised by very low trust in police.

South Africa’s 2020/21 Victims of Crime Survey (VOCS) was published last month. Although its accuracy was affected by the coronavirus pandemic, the findings on experiences of crime and perceptions of safety and gender-based violence remain valuable.

Although the South African Police Service has a well-established data-capturing and analytics capacity, these are only as effective as the information police receive and process. In South Africa, as elsewhere, much crime is never reported, and when it is, police don’t always record it. So beyond murder figures, police crime statistics are limited as a measure of actual crime levels.

This is one reason why victim surveys are valuable. In 2021 trust in police dropped to an all-time low of 27%. The VOCS is one of the best ways to determine how this loss of confidence impacts the reporting of crime to police.

The proportion of people who said they trusted police dropped to an all-time low of 27%

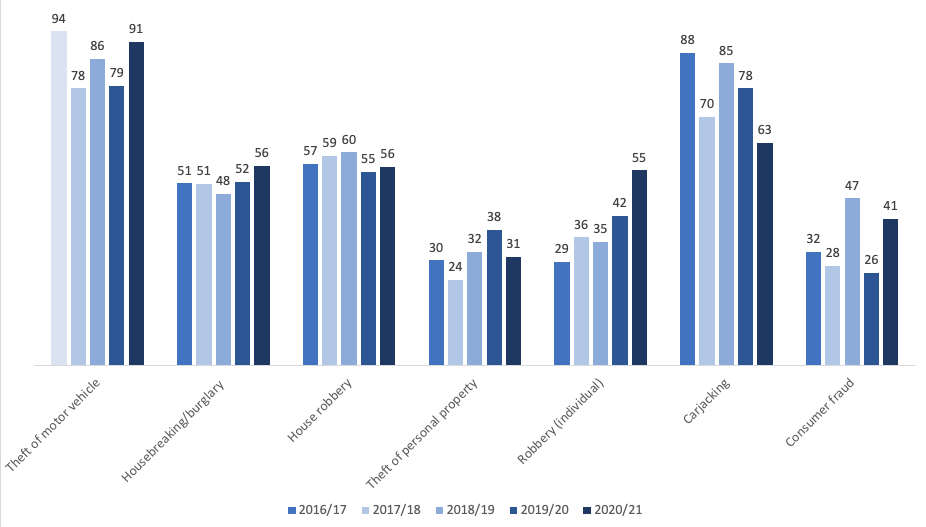

In general, crimes such as motor vehicle theft or hijacking are reported at higher rates than offences like house or street robbery. This is not because vehicle crimes are more important or traumatic. Instead, it’s because the minority of South Africans who own vehicles are likely to have their property insured and so have a financial incentive to report.

Poorer households could place greater value on kettles, cellphones or personal items stolen during home invasions. But they don’t have insurance or believe the police will provide empathy or support if they report the offence to them.

Although trust in police is low, the latest VOCS suggests increases in reporting of vehicle theft, street robbery and consumer fraud. This may partly be explained by the disruption of established crime and reporting patterns during South Africa’s 2020 coronavirus lockdowns.

Chart 1: Percentage of victims who reported crime to police, 2016-2021  (click on the graph for the full size image)

|

Chart 2: Percentage of respondents who felt safe walking alone in their area during the day and night  (click on the graph for the full size image)

|

The pandemic may also have affected the VOCS’ valuable perception data, such as questions exploring feelings of safety. A five-year trend suggests a notable increase from 29% of people feeling safe at night in 2016/17 to 40% in 2020/21 (Chart 1). Some may have felt safer in their residential area if interviewed during a hard lockdown in 2020 when streets were busier and surveillance persistent.

Asked if they had taken measures to protect themselves against crime, only a third of respondents said yes, with most of those saying they felt safer after changing their habits. The changes included walking during ‘safer hours’ (45%) and being ‘more alert of my own surroundings’ (22%). Again, the nature of public spaces changed dramatically during various phases of the pandemic, perhaps affecting these answers.

‘Whites’ or ‘Indians/Asians’ were more likely to have taken measures than were ‘Coloureds’ or ‘Black/Africans’. This disparity may reflect how middle and affluent classes can opt out of public spaces and transport more easily than poorer South Africans.

Another valuable set of questions explores gender-based violence – a significant problem in South Africa. Promisingly, 91% of respondents had been exposed to campaigns ‘about violence against women and children’; 99% believed that all violence against women and children should be reported; and 93% thought people should call the police if they witnessed violence at a neighbour or friend’s residence.

What is less encouraging is that only 65% said people should intervene in such violence themselves. This implies an unsurprising disconnect between how South Africans think and feel about violence and how we act when faced with it.

Asked how they would respond in the face of a male friend ‘insulting or verbally abusing a woman he was in a relationship with,’ most said they would feel uncomfortable but probably not say or do anything.

It’s easier for middle classes to avoid public spaces and transport than for poorer South Africans

Similarly, most respondents believed fathers should ‘play a role in raising children;’ that women and men should have the same chance of ‘being elected to political office;’ and that ‘having an income is the best way for a woman to be an independent person.’ Unfortunately however, 55% also agreed with the statement that, ‘If a woman earns more money than her man, it is almost certain to cause problems.’

This last finding undermines the sentiment of gender equality implied in previous answers. And the use of the phrase ‘her man’ by Statistics South Africa assumes a sense of ownership and power inequality between genders, possibly unconsciously held by the survey drafters.

The same bias is apparent when asking whether it’s acceptable ‘for a man/husband to hit or beat his woman/wife.’ Nearly 10% of respondents thought such violence was acceptable in specific contexts, such as sexual infidelity.

That the question was framed in only one form and direction (a man assaulting a woman) embeds assumptions about domestic violence, intimate partnerships (that they are heterosexual) and sexual identity (that all people with male bodies identify as ‘man’).

While most survey respondents (83%-88%) said they ‘were aware of’ services available to victims of gender-based violence such as medical care, protection orders and counselling, only 47% knew of shelters and places of safety. Notably, the survey only asked about awareness of services, not whether people knew how to access them.

There is a disconnect between how people think about violence and how they act when faced with it

Overall, most victims and perpetrators of all types of violence are men. As long as South African boys and men continue believing violence is a legitimate means to express authority and solve problems, it is unlikely that violence against women or children will decrease, despite some of the promising findings mentioned above.

Public safety governance cannot be based on police statistics alone, and the government is to be commended for investing in a diversity of crime- and violence-measurement tools, including the VOCS. However, the VOCS, like police data, should be interpreted and acted on with caution – especially this latest iteration.

Ideally, police and VOCS data should be compared to violence-related injury data from health facilities, bank and insurance data on property and financial crime, and other quality perception surveys. Alone, none of these data sets reveals ‘the truth’ about crime, violence or risk, but together they move us a little closer to it.

Andrew Faull, Senior Researcher, Justice and Violence Prevention, ISS Pretoria

Exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles have been given to Daily Maverick in South Africa and Premium Times in Nigeria. For media based outside South Africa and Nigeria that want to re-publish articles, or for queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.

Image: © Aron Hyman

Development partners

This article was published with funding from the Hanns Seidel Foundation and the Bavarian State Chancellery. The ISS is also grateful for support from the members of the ISS Partnership Forum: the Hanns Seidel Foundation, the European Union, the Open Society Foundations and the governments of Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden.