Is South Africa equipped to deal with the new challenges of peacekeeping?

Political commitments need to be balanced with capabilities if South Africa is to meet the changing demands of peacekeeping operations on the continent.

Published on 27 September 2013 in

ISS Today

By

Violent conflict remains a problem throughout Africa and shows no signs of decreasing. In a recent ISS paper on conflict trends, Cilliers and Schunemann reported that conflict in Africa was becoming increasingly fragmented and that the number of non-state actors involved in these conflicts was rising. Insurgent groups also have strong transnational characteristics and are quick to change, form new alliances and shift allegiance to suit their agenda, making it difficult to build a coherent intelligence picture.

For the foreseeable future, intrastate violence is likely to continue in poor countries with weak governance, previous experience of conflict, spillover from bad neighbourhoods and widespread youth unemployment and exclusion. The combination of these factors will, in all probability, lead to longer, more drawn-out conflicts, which will in turn necessitate more costly peacekeeping operations.

Peacekeeping operations have evolved to combat such conflicts. Since 2011, ten new peacekeeping operations have been deployed to eight African countries, while over 50 have been deployed since 2000 by a variety of organisations, including the United Nations (UN), African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). These organisations are also increasingly undertaking what used to be termed ‘partnership peacekeeping’.

However, the nature of armed conflict is changing and peacekeeping operations need to adapt to produce more flexible and realistic solutions to emerging threats. Africa, and South Africa in particular, is beginning to play a more robust role in peacekeeping, but is it equipped to adapt to new peacekeeping challenges? As South Africa moves ahead as a peacekeeping player, it will have to grapple with a number of wider issues in terms of the changing nature of peacekeeping and the implications for more robust engagement.

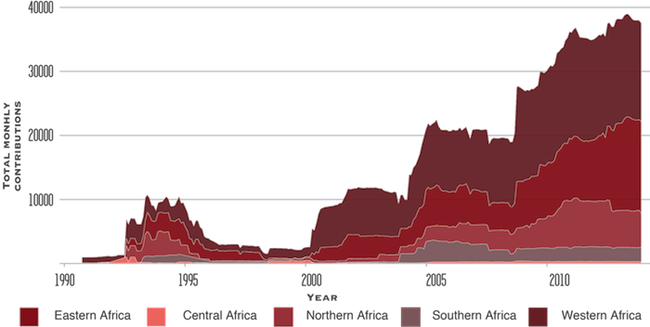

African peacekeepers now feature more prominently in peacekeeping operations than ever before. The UN, the greatest contributor to peacekeeping operations, has shifted from using predominantly Western troop-contributing countries, reluctant to deploy their own soldiers, to African personnel. Data collected by the International Peace Institute shows that the number of African countries contributing to UN peacekeeping has doubled from 2002 to 2008, surpassing European countries.

Graph 1: African countries contributing to UN peacekeeping (Graph courtesy of the International Peace Institute)

The AU now places a growing emphasis on its African Peace and Security Architecture and the conceptualisation of an African Standby Force. Meanwhile, South Africa is increasingly viewed as a key regional actor in terms of peacekeeping, despite only entering the scene in 1998 with an intervention in Lesotho. It has subsequently contributed troops to the UN for MONUC and MONUSCO (Democratic Republic of Congo, or DRC), ONUB (Burundi), UNMEE (Eritrea and Ethiopia), UNAMID (Darfur), ONUCI (Côte d’Ivoire) and UNMIL (Liberia), as well as other peacekeeping missions. It has also provided an average of 1 500–2 000 uniformed UN peacekeepers a year, becoming the eighth largest African contributor.

Lotze, de Coning and Neethling note that South Africa’s engagements have been informed by its political efforts at conflict prevention and its view of itself as an emerging middle power. They point out that South Africa has also deployed peacekeepers through a variety of regional or bilateral arrangements rather than restricting itself to UN deployments.

Despite its controversial deployment of 265 troops to the Central African Republic (CAR), in which 13 soldiers died and 27 were injured, South Africa has continued to deploy troops to the DRC under the newly mandated Force Intervention Brigade (FIB). Although South Africa deployed in the CAR on the basis of a bilateral agreement whereas in the DRC it has deployed under UN Security Council Resolution 2098, the country’s willingness to contribute troops despite tensions following events in the CAR demonstrates its determination to position itself as both the political and the peacekeeping powerhouse of the region. However, with a mandate to neutralise all armed insurgents (with numbers estimated at between 4 000 and 14 000) in the DRC, the FIB’s 850 soldiers seem inadequate, as does the brigade’s equipment.

The changing nature of conflict poses challenges that require an adaptation of traditional peacekeeping methods. Heitman has noted that non-state actors, often referred to as rebels, are increasingly well trained, experienced, well armed and equipped, and operating on their home turf. In turn, South Africa’s deployment with the FIB also represents a shift to more robust peacekeeping; one that employs the principles of peace enforcement and limited war-fighting tactics rather than traditional peacekeeping activities. This implies the use of force, which is accompanied by a greater risk potential for troops, observance of the Geneva Conventions (law of war) as an active role player, and a constant need for troops to balance their actions with humanitarian principles.

How will South Africa adapt to these challenges and does it have the capacity? Should it engage via the UN or the AU? How can cooperation between these organisations be improved? What equipment will be needed? It is important to note that regional economic communities (RECs) have become vital in peacekeeping. In fact, the FIB was created through Southern African Development Community (SADC) troop contributions, even though it was under a UN Security Council resolution mandate. Yet, for the moment, the UN Security Council engages with the RECs only via the AU. South Africa’s increasing influence in peacekeeping may eventually change this dynamic. Of course, it will take considerable change to overcome the problem of the lack of a united African voice at the UN Security Council.

In terms of new equipment, the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) UN Infantry Battalion manual notes that modern equipment, including unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), air reconnaissance, night vision and radar scanning, is needed in future peacekeeping operations. As Leijenaar points out, hybrid AU and UN peacekeeping operations may result in a situation where troop-contributing countries are expected to deliver technologically advanced forces that they cannot afford.

In the past, there have been instances where South Africa was unable to recover the full reimbursement from the UN peacekeeping operations because its equipment failed to meet UN serviceability standards. At the same time, the South African National Defence Force’s (SANDF) budget has been overstretched in recent years and already lacks key equipment such as UAVs, many vehicle types and air and sea lift equipment. How South Africa balances its commitments with its capabilities will be critical for future engagement. In addition, South Africa will have to manage its domestic politics, the increasing borderline protection responsibilities requiring a mooted 22 troop companies, growing scrutiny over government spending and local perceptions as to its intentions, with its continental and global aspirations.

The demand for more robust, better-trained and better-equipped peacekeeping forces to deal with situations such as the Mali intervention or the M23 rebels in the DRC, means that South Africa needs more than just political will to become a major continental role player in an increasingly complex conflict management environment – it also needs urgent investment to operationalise its military forces to enable robust peace enforcement. This includes force enablers like UAVs, new log and APC vehicles, attack helicopters, mortar/artillery locating radar, special forces, medium airlift and artillery; and the relevant integrated concept of Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR), which enables combat advantage on the battlefield – all of which are in increasing demand in peace missions.

Amanda Lucey, Researcher, Conflict Management and Peacebuilding Division, ISS Pretoria

Media coverage of this ISS Today:

DefenceWeb