Replicating global responses to COVID-19 may not work for Africa

Containing the virus in Africa requires focusing on vulnerable communities and context-specific responses.

The first case of COVID-19, now a global pandemic present in 199 countries, was reported in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. Africa’s first confirmed case was in Egypt on 15 February. The first sub-Saharan case was reported in Nigeria on 28 February.

Information to date confirms that older people are more susceptible to severe effects of the disease. However people of any age with underlying health issues are at risk of complications. Could sub-Saharan Africa’s largely young population work in its favour if the local spread can be contained?

With over 723 287 cases confirmed globally by 30 March, COVID-19 is having far-reaching effects. Apart from over-stretching even the best health systems, causing unprecedented mortality rates and constraining liberties like freedom of movement, it is clear that a global recession is happening.

As the coronavirus spreads rapidly across the world there seems to be a similar upward trajectory in several countries. According to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, case counts in the United States (US) and Germany for example have been growing at the same rate since hitting the 100+ mark. Cases in the US have now surpassed those of China and Italy. Live updates by country can be found here.

African countries seemed insulated for a time, but are now recording a rapid increase in new cases. But they may have found themselves slightly more prepared than if the virus had arrived months earlier than other regions.

Economic and socio-political consequences will be dire if a vaccine isn’t found soon

As part of their central response, airport screening especially for flights from Europe was made mandatory. It’s now clear though that this alone wasn’t enough – there were no proper mechanisms of isolation and contact tracing for travellers who were directed to ‘self-isolate’ in many countries.

Despite the head start, it’s hard to imagine that African countries have the pandemic under control and that they are acting speedily and decisively. The continent’s weak health systems, high rates of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis infections, poverty and a large informal economy and settlements without adequate water and sanitation infrastructure pose huge challenges to containing the spread of the disease.

However Africa has had experience with other health pandemics like Ebola, which might provide information and strategies to cope with COVID-19.

The numbers are now rising quickly (Figure 1) and scientists are unsure about how the virus will behave, given the disproportionate challenge of other infectious diseases in Africa, and the difficulty of what has now moved from ‘social distancing’ to ‘physical distancing’. This is owing to overcrowded cities and informal settlements, and the inability of the most vulnerable to skip work even for a day. It appears to be a ticking time bomb.

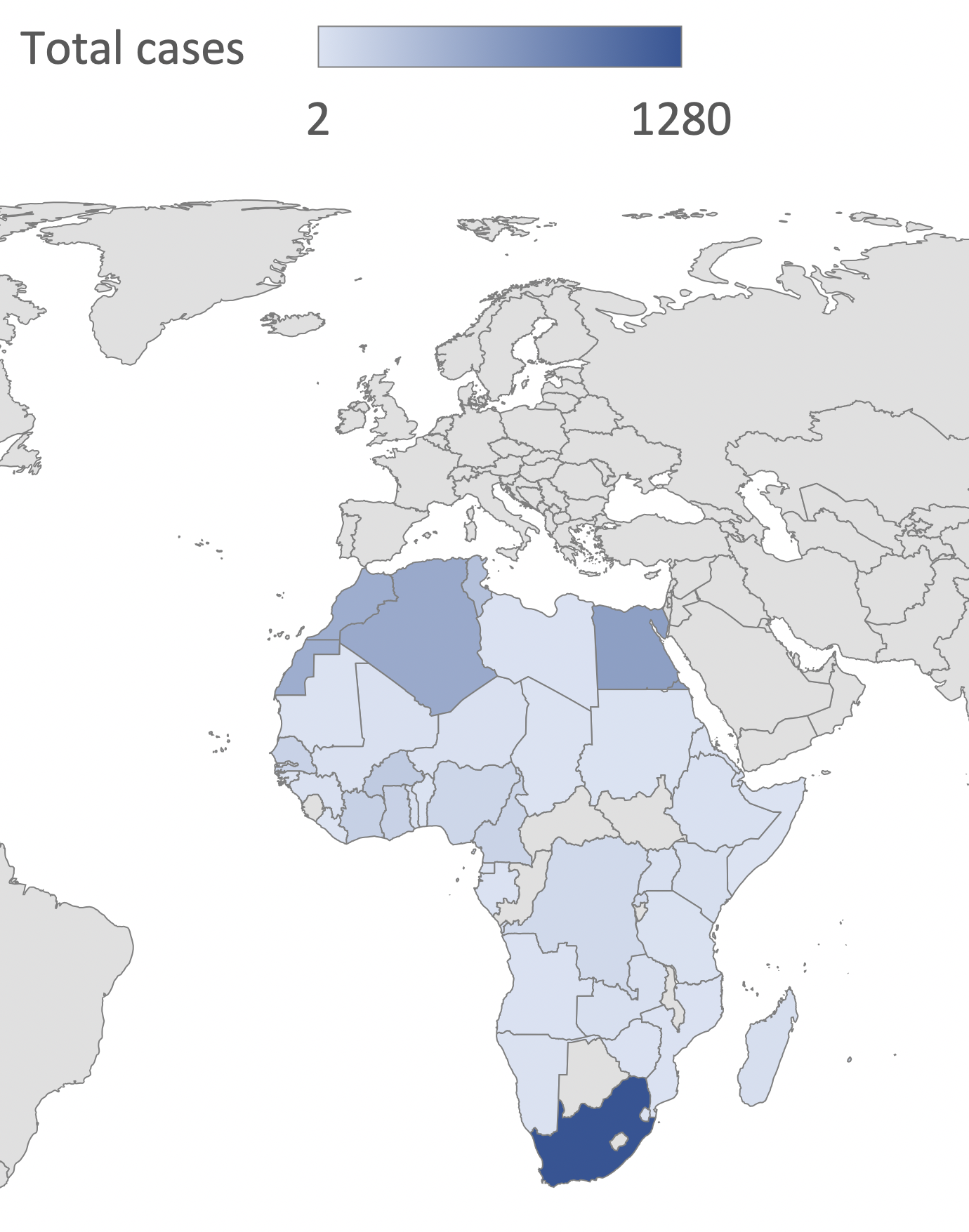

South Africa and countries in North Africa have so far recorded more cases in part because they had more traffic with Europe and probably because more tests have been conducted than in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 2).

So far, attention has been focused on hospitals and their intensive care unit capacity. Although important, greater focus should be speedily geared towards communities, especially the vulnerable, to avoid overwhelming already weak health systems.

Figure 2: COVID-19 cases in African countries  (click on the map for the full size image)

|

If Africa follows the trajectory of China, Italy, Spain and the US, it would take approximately one month or less to reach 82 000 concurrent cases – which could collapse the health system in a country like South Africa which has the best health system on the continent. And that would be a best-case scenario.

Apart from Rwanda, which first instituted a lockdown and banned travel between cities and districts, and most recently South Africa, Lesotho and Zimbabwe, people are still moving freely between regions within countries, thus facilitating the spread of the disease. Given these circumstances, it may just be a matter of time before community spread escalates, particularly among workers who take crowded public transport to their homes in low-income areas or rural areas where most old people live.

Can African governments go beyond mimicking global responses – which are important – to more context-specific ones? Africa’s sense of social solidarity and community, experience with health pandemics, its youthful population and their dynamic online activism are some of the resources that can be harnessed at community and national level to spread information and better manage the crisis on the continent.

There is no telling how long the virus will take to run its course, but there’s no doubt that the economic and socio-political consequences are going to be dire if a vaccine is not found soon. In the meantime, African countries and their citizens must take this more seriously. Ways must be found to incentivise poor and vulnerable communities to stay at home to avoid further spread of the disease – the cost of which would be massive.

Stellah Kwasi, Researcher, African Futures and Innovation, ISS Pretoria

In South Africa, Daily Maverick has exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles. For media based outside South Africa and queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.

Picture: Amelia Broodryk/ISS