How to get Ethiopia’s Transitional Justice process back on track

The government’s renewed commitment to transitional justice efforts should lead to a carefully planned and sequenced resumption of the paused process.

Published on 28 November 2025 in

ISS Today

By

Tegbaru Yared

Researcher, Horn of Africa Security Analysis, ISS Addis Ababa

In May 2025, as Ethiopia’s Ministry of Justice neared completion of key legislative frameworks, speculation emerged that government might prioritise national dialogue over transitional justice. The dialogue process is now scheduled to conclude in February 2026, following a one-year Parliament-approved extension.

The pause on transitional justice led to perceptions in policy circles that some officials – even the National Dialogue Commission – viewed transitional justice as an outcome or recommendation from the dialogue, rather than a distinct, indispensable peacebuilding process.

However, in his address to Parliament on 28 October, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali reaffirmed that Ethiopia’s peacebuilding agenda comprised three interrelated pillars: national dialogue; transitional justice; and disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR).

He said transitional justice was designed to address past atrocities, while the national dialogue aimed to reach consensus on contested governance, state and nation-building issues. The DDR process focuses on security stabilisation and reintegration of ex-combatants.

Abiy’s remarks offered long-awaited conceptual clarity, reaffirming that transitional justice was both a central pillar and an autonomous process in Ethiopia’s peacebuilding framework. This countered earlier assumptions that transitional justice was an outcome of dialogue – a problematic misconception for three main reasons.

Transitional justice is both a central pillar and an autonomous process in Ethiopia’s peacebuilding framework

Firstly, it risked further undermining the credibility of the national dialogue – already questioned for its inclusivity and independence – by implying that the process was intended to produce a predetermined outcome: the transitional justice process.

Secondly, pausing an ongoing transitional justice process only to reintroduce it later as a dialogue recommendation would amount to a retroactive attempt at claiming ownership rather than advancing justice.

Thirdly, conflating the two would delay accountability, marginalise victims, and transfer the dialogue’s procedural and representational shortcomings into the transitional justice process.

At the same time, the transitional justice landscape has grown increasingly opaque. The Justice Ministry has paused development of key legislation and has issued no public updates for months. Civil society organisations have remained largely inactive, despite their formally assigned roles under the 2024 Transitional Justice Policy.

The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) seems to be the only institution actively engaged in public awareness and civic participation. Its commendable efforts risk becoming fragmented without clear governmental direction. Meaningful progress for the transitional justice process requires formal endorsement and coordinated action across state institutions.

To help address this gap, the EHRC should continue advocating for a stronger role for civil society and the expansion of civic space, while enhancing its cooperation with the Justice Ministry and other state institutions to clarify the process’s status and support its continued implementation.

A formal resumption of the transitional justice process – expected by early 2026, once the national dialogue’s extended time expires – must be guided by principles of complementarity and sequencing. Independence among the three peacebuilding pillars does not imply isolation. Transitional justice, national dialogue and DDR must advance coherently, reinforcing one another.

|

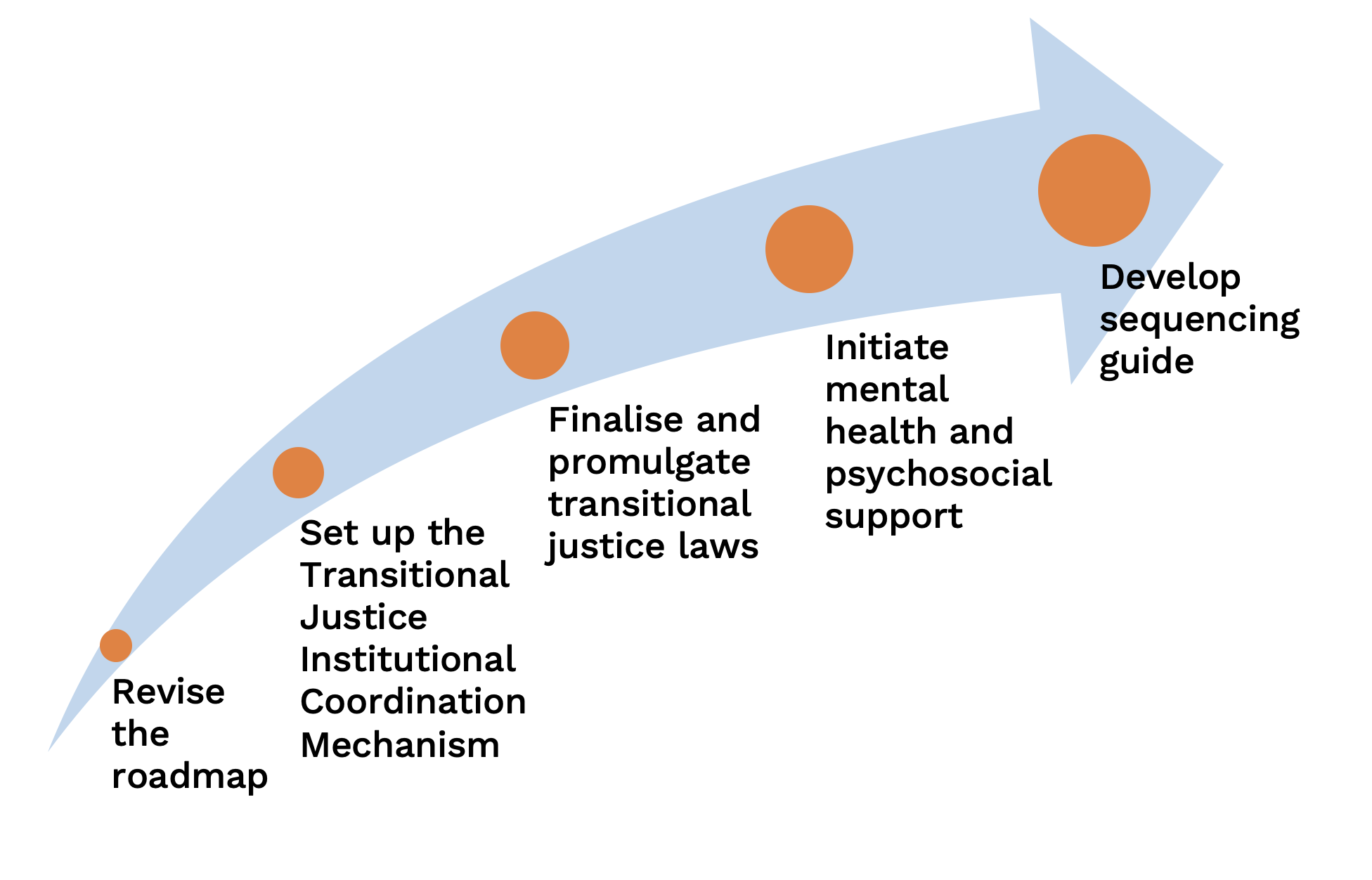

Considerations for resumption of Ethiopia’s transitional justice process

|

Transitional justice, anchored in truth-seeking, accountability, reparations, and institutional reform, will remain incomplete if detached from the political and security contexts shaped by the national dialogue and DDR processes. Likewise, the dialogue and DDR cannot secure lasting peace without credible justice and meaningful redress.

A standalone parallel transitional justice process would complement rather than obstruct the dialogue’s outcomes. Should the dialogue produce recommendations on justice, redress, or reconciliation, these could be integrated into the transitional justice framework, maintaining coherence while ensuring both processes remain distinct yet mutually reinforcing.

Building on complementarity, the immediate priority should be to finalise and review the draft transitional justice laws. Once enacted by Parliament, key mechanisms such as the Special Bench, Special Prosecution Office, Commission on Truth-Seeking and Social Cohesion (encompassing amnesty and reparations), and Vetting Commission could be established.

Legal codification is vital for a holistic state approach – creating parliamentary ownership of the process and ensuring participation from the justice, defence, security, and women’s and social affairs ministries, alongside civil society organisations, regional institutions, and victim associations. This transition from policy to practice must be accompanied by an updated implementation roadmap building on the 2024 version.

The Justice Ministry should use the current pause as an opportunity for course correction

Simultaneously, establishing the multi-stakeholder Transitional Justice Institutional Coordination Mechanism envisioned in the policy is essential for sustained coordination and collaboration, and to guide the creation and operationalisation of the new transitional justice institutions. This 13-member body will formally include representatives from civil society, academia, and the Human Rights Commission, alongside key state institutions such as the judiciary, Parliament, and executive.

Next would be to provide psychosocial and mental health support (MHPSS) for victims of violence. Prioritising MHPSS acknowledges widespread collective trauma, provides tangible relief, and lays the foundation for trust-building and future participation in truth-telling and accountability mechanisms.

Although the 2024 policy doesn’t specifically designate MHPSS, forthcoming legislation should address this gap by institutionalising psychosocial support as both a standalone and a cross-cutting component of a victim-centred approach.

Sequencing will be critical after legal enactment. The interlinked components of transitional justice require a phased implementation tailored to Ethiopia’s evolving context. To ensure predictable and coordinated implementation, a clear sequencing guideline should be developed and made public. Such a strategy would provide transparency, enable monitoring, and strengthen public confidence in the process.

Dealing with past abuses is not an appendage of national dialogue, but an autonomous process

Beyond considerations on complementarity and sequencing, the Justice Ministry and other stakeholders should use the current pause as an opportunity for course correction. The hiatus provides the chance to reflect on implementation gaps identified during the first phase of the process.

These include limited public communication, weak inter-agency coordination, limited clarity regarding decentralisation of the process, and the absence of a coherent strategy for integrating traditional justice mechanisms.

The pause should enable the Justice Ministry to strengthen its internal technical capacity, establish a dedicated department for transitional justice, re-engage regional stakeholders, refine the sequencing and prioritisation of activities, and develop a more transparent and inclusive roadmap. This would enhance public confidence and ensure a more coherent, coordinated, and well-grounded resumption of the process once it formally restarts.

Ultimately, government has reaffirmed that dealing with past abuses is not an appendage of the national dialogue, but an autonomous process grounded in accountability, victims’ rights and institutional reform. The challenge lies in translating this political commitment into concrete action through carefully planned, strategically sequenced recommencement of the transitional justice process.

Exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles have been given to Daily Maverick in South Africa and Premium Times in Nigeria. For media based outside South Africa and Nigeria that want to re-publish articles, or for queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.