How a Boko Haram faction entrenched itself near Nigeria’s capital

New evidence shows how JAS’ Shiroro cell adopts a flexible approach that tolerates local bandits and their vices.

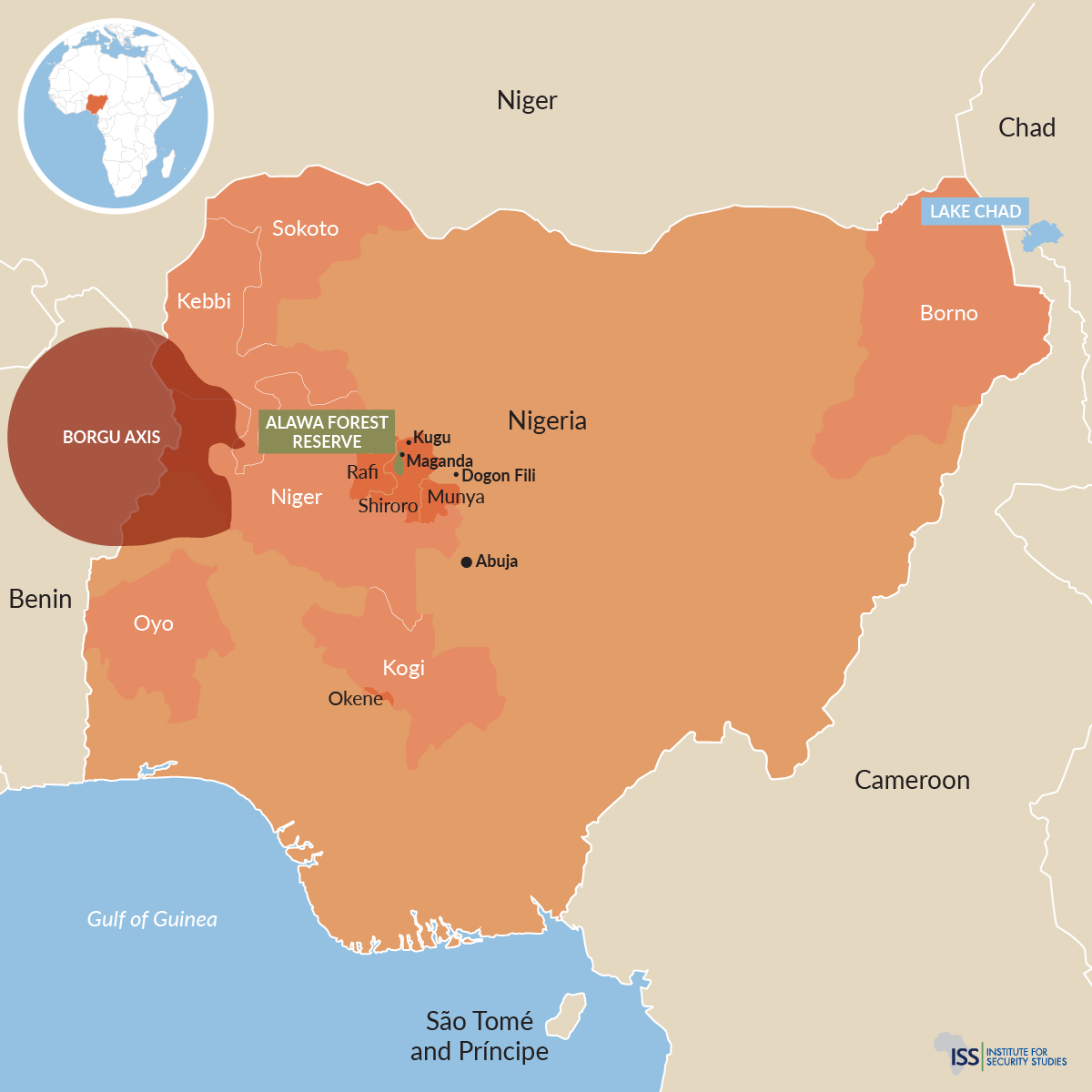

The Shiroro cell of a Boko Haram faction in Niger State, near Nigeria’s capital Abuja, is the group’s furthest and most successful expansion outside the Lake Chad Basin. Until now, information about the cell of the Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (JAS) group sketched its existence, but left many questions unanswered.

New evidence from ongoing Institute for Security Studies (ISS) research includes interviews with defectors, local victims and women who escaped JAS after being married to some of its fighters. The information sheds light on the Shiroro cell’s operations and alliances, and what they mean for counter-terrorism in Nigeria.

Audiovisual material and corroborating reports show JAS embedded deeply in Niger State’s forested communities, blending jihadism with local Fulani banditry – the main source of insecurity in the area. By tolerating the bandits’ non-adherence to its strict religious code, JAS benefits from their weapons, fighters and knowledge of the local terrain, enabling the group to gain a strategic foothold in Central Nigeria.

JAS has embedded deeply in Niger State’s forested communities, blending jihadism with local Fulani banditry

The cell is led by Abubakar Saidu, alias Sadiku. A native Babur from Biu in Borno State, Sadiku was sent to Niger State in 2014 by late JAS leader Abubakar Shekau. He was part of a seven-man team directed to meet remaining members of the ultra-Salafist Darul Islam group. After being dislodged from its headquarters in Mokwa by a 2009 police raid, members had fled north into Nigeria’s largely ungoverned forests.

Although Darul Islam had earlier rejected Boko Haram’s overture for alignment, Sadiku found fertile ground among its dispersed followers and started the Niger State cell along with his comrades from Borno. He began shuttling between Borno and Niger states, gradually embedding himself in the Alawa Forest Reserve area, and coordinating with the local Fulani. This culminated in escalating attacks by the group in 2021.

From forest camps like Kugu and Dogon Fili, the group attacks security forces and civilians in villages and towns, and on roads in Shiroro, Munya and Rafi local government areas. It has killed hundreds, displaced thousands and planted many improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

A Premium Times investigation and ISS interviews reveal the abduction of boys who are forced into an indoctrination programme at Islamic schools, and forced labour. Women and girls are kidnapped and forced into marriages with fighters.

|

Strongholds of JAS' Shiroro cell in Niger State, Nigeria

|

Unlike the doctrinal and tighter command discipline of rival Boko Haram faction Islamic State West Africa Province’s (ISWAP), JAS thrives on ideological fluidity and predation. Militants raid villages, carrying out kidnapping and extortion, which they justify as ‘fayhoo’ (spoils taken from civilian ‘unbelievers’). This flexibility appears key to its entrenchment in Niger State.

The fusion of jihadists and non-ideological armed criminals is not new. In Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso, jihadists have worked with local criminals for a stake in illegal gold mines. But the Shiroro cell’s local integration stands out, especially its tolerance of the bandits’ use of alcohol, drugs and prostitution, which contravene the cell’s strict religious doctrine.

A woman formerly married to a fighter recalled Boko Haram clerics from North East Nigeria expressing disapproval, but Sadiku argued that the Fulani would ‘change with time.’ It is however doubtful whether the bandits would ever cooperate with jihadists out of religious conviction.

The Shiroro cell is not structured under the traditional Boko Haram command system, but under kachallas (warlords or strongmen), which shows an embracing of bandit terminology. Notorious bandit leader Dogo Gide served under Sadiku as kachalla before their fallout – though ISS interviews suggest that Bakura Doro, the Lake Chad-based overall commander of JAS, may be mediating a reconciliation.

The Shiroro cell is dispersed across forest communities to avoid detection by Nigeria’s largely aerial military campaign

According to defectors and women who lived in the camps, Doro supplies weapons from his base on Lake Chad’s Barwa Island. One video, seen by ISS, shows weapons wrapped in grass and fish, hidden on boats bound for Shiroro.

This arms flow is complemented by locally sourced weapons, seized from security forces or trafficked through Sahelian smuggling networks, using the group’s bandit alliances. Money also flows from Shiroro to Doro, underscoring how territorial expansion is a tactic to also finance terrorism.

The Shiroro cell is dispersed across forest communities, including Kugu, Maganda and Dogon Fili, to avoid detection by Nigeria’s largely aerial military campaign. The military’s ground assets were withdrawn after facing repeated deadly attacks.

Further complicating the situation is the Lakurawa, a Sahelian-rooted Fulani armed group designated a terrorist organisation by Nigeria in 2025. While espousing jihadism, Lakurawa is predatory and operates in northwestern Sokoto and Kebbi states along the Niger Republic border.

According to a defector and an expert on the conflict, Lakurawa’s emissaries have visited Sadiku in Shiroro annually since 2023, providing the first credible evidence of Lakurawa-JAS interactions and possible alignment. Sadiku sent fighters to reinforce Lakurawa, which in turn approached another notorious Fulani bandit leader, Bello Turji, ostensibly to replicate the JAS-style alliance in the country’s North West.

Nigeria’s strategy to prevent and counter violent extremism cannot remain largely focused on Lake Chad

The convergence of armed groups raises the threat of a wider coordination of violence. The 2022 Kuje prison attack in Abuja involved a rare ISWAP-JAS-Ansaru collaboration. A defector who participated in the 2022 Kaduna train attack and kidnapping, told ISS the assault was executed by Sadiku’s fighters using IEDs from Borno, and partnering with bandits.

Meanwhile, ISWAP has long sought to expand beyond Lake Chad, even targeting southern states like Oyo to access coastal West Africa. ISS research shows it sent five commanders with 25 fighters each to Central Nigeria in April, maintaining a presence in Kogi’s Okene axis. Yet its success has been limited compared to JAS’ Shiroro stronghold.

Geography amplifies the Shiroro threat. Niger State connects north and south Nigeria and borders Benin through porous forest corridors linking to the Sahel. Arrests in July of Boko Haram-linked women heading to the Borgu axis suggest the cell is eyeing broader expansion.

Yet, Nigeria’s strategy to prevent and counter violent extremism remains largely Lake Chad-focused. The Shiroro case shows the need for a recalibrated threat map. Responses must include forest surveillance, road security and partnerships with local vigilantes under accountability frameworks. Finance routes must be disrupted, and gender-responsive reintegration programmes must be run for defectors.

Exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles have been given to Daily Maverick in South Africa and Premium Times in Nigeria. For media based outside South Africa and Nigeria that want to re-publish articles, or for queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.