From Djibouti to Jeddah, the Western Indian Ocean needs security

Lessons from successful state collaboration against piracy must be extended to other maritime threats.

Published on 23 May 2018 in

ISS Today

By

Timothy Walker

Senior Researcher, Transnational Threats and Organised Crime, ISS

Crimes like piracy, illegal fishing and the smuggling and trafficking of firearms, narcotics and people continue to threaten security in the Western Indian Ocean. If left unopposed, they severely hamper shipping and the growth of blue or ocean economies.

Yet there are fundamental security options in place, for example in the Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCoC) and its 2017 Jeddah Amendments (DCoC+). And while participating states may have different priorities regarding the ocean’s threats, combined efforts and stronger national capacities could improve maritime security overall.

At a meeting this month in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, signatories explored how they could build on years of successful counter-piracy cooperation to create a regional maritime security architecture to tackle all crimes. The meeting also discussed the question common to all maritime codes, conventions and strategies – how to move from declarations of intent to effective action.

The Jeddah Amendments show political appetite to combat maritime crimes in the Western Indian Ocean

Twenty littoral countries of southern and eastern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula adopted the original DCoC in January 2009. Many have limited naval or maritime security capacity. The code provided the basis for enhanced national and regional inter-agency cooperation, information sharing, capacity building and training. The result was more effective collaboration among states to combat piracy and armed robbery at sea.

The DCoC+ amendments now cover other important transnational maritime crimes including the trafficking of arms and narcotics, the illegal wildlife trade, illegal oil bunkering and theft, human trafficking and smuggling and the illegal dumping of toxic waste. These changes showed that despite cultural divides and historical disputes, states could agree on common maritime security goals. The Jeddah Amendments suggest an increasing political appetite to strengthen the institutions needed to combat maritime crimes.

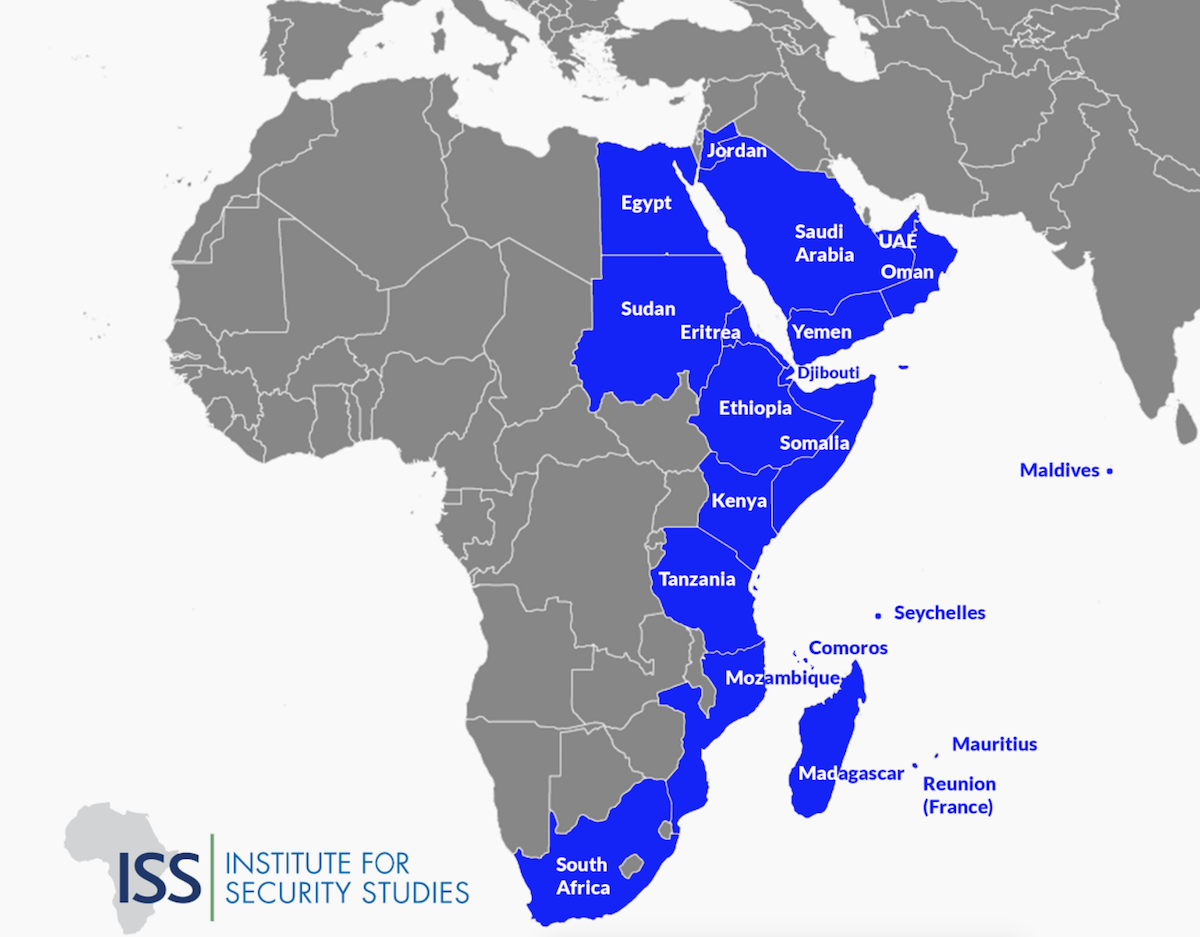

The code of conduct brings together a wide range of Western Indian Ocean states (see map). It is a global effort facilitated by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) and developed by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the African Union (AU), the African regional economic communities, the European Union and INTERPOL, to name a few.

States eligible to sign the Djibouti Code of Conduct

The 2018 DCoC+ meeting highlighted several challenges for signatories and stakeholders. States debated whether they should widen the code’s counter-piracy provisions to include non-traditional threats like illegal fishing and dumping of toxic waste. This is in light of the drop in piracy incidents from 2012, the existence of other major maritime security threats in the region, and the growing interest in benefiting from the blue economy.

How the code will play out in practice is still unclear. The DCoC+ is not a binding legal instrument. Threats vary from country to country, and participating states differ on the definition and purpose of maritime security. For instance, some countries like South Africa continue to consider piracy a major threat. Others now focus on illegal fishing or the trafficking of narcotics.

The common question is how to move from declarations of intent to effective maritime action

This means that while states agree that a wider array of crimes be tackled, they might choose to focus on only one or two based on their particular understanding of the code’s purpose. More agreement on these priorities is needed for the code to be effective.

Member states should also contribute to and steer the DCoC+ as a national priority. To achieve regional security, states must develop stronger domestic capacities. This includes integrated maritime security strategies and policy and operational coordination committees.

The DCoC+ is also not the only maritime security or governance framework in the region. It is part of many maritime initiatives like the UNODC’s Indian Ocean Forum on Maritime Crime, the Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia, and the work conducted in the Indian Ocean Rim Association or the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium.

There are also several African regional economic communities pursuing maritime interests, as well as the AU itself with its 2050 Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy and the Lomé Charter. Duplication of efforts must be avoided. Synergies between countries with limited capacity for maritime security or governance should be encouraged.

Three key states are not members of the amended Djibouti Code of Conduct – Iran, Pakistan and India

The integration of other states into the code as observers or participants also needs to be considered. Three key Western Indian Ocean littoral states are not members of the code – Iran, Pakistan and India. If the DCoC+ doesn’t involve these states, they might pursue their interests in other organisations which could mean a duplication of efforts.

Another important issue is the relationship between the DCoC+’s three information sharing centres and other similar regional initiatives. The centres are key to the code’s success, but they lack visibility and haven’t yet fulfilled their potential. Other information centres, like the EU’s Maritime Security Centre Horn of Africa and the recently opened centres in Madagascar and Seychelles, funded by the EU Programme to Promote Regional Maritime Security, are likely to handle most regional information sharing tasks.

Yet the DCoC+ can provide the framework for linking all information sharing centres. It can also provide lessons from best practices for other collective maritime security efforts, such as West Africa’s Yaoundé Code. If states tackle these issues, the 2018 Jeddah meeting could prove effective beyond piracy and the Indian Ocean to apply to West Africa too, and thus Africa as a whole.

Christian Bueger, Professor of International Relations at Cardiff University and the director of SafeSeas and Timothy Walker, Senior Researcher, Peace Operations and Peacebuilding, ISS Pretoria

In South Africa, Daily Maverick has exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles. For media based outside South Africa and queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.