Better police use of data could cut South Africa’s crime

A new report finds concerning flaws in point-level police data from areas with high rates of violence.

Each year in September, the South African Police Service (SAPS) releases crime statistics for a 12-month period ending on 31 March, which means the data is five months out of date when it reaches the public. When crime levels increase (as they have this year), headlines lament. When any decreases are seen, these are linked to strategic efforts by the police.

Nationally, murders have risen by 3.4% since 2017-18 and are 35% higher than in 2011-12. The 21 022 murders average out to 58 killings every day across the country. However, these murders are not evenly spread across time and space. Over half (56%) of murders happen on the weekend. Spatially, a small number of police stations bear a disproportionate share of violent crime.

In the latest statistics, the 30 police stations reporting the highest numbers of murders (roughly 3% of all stations) account for 21% of the total. As one example among these, the Greater Khayelitsha area (comprising three police stations – Khayelitsha, Harare and Lingelethu West) experienced an annual murder increase of 20%.

Yet even station-level figures mask critically important patterns of crime that can only be studied through accurate point-level crime data. This data records each crime by type, exact geographic location and exact date and time of the incident.

In Trinidad and Tobago, hotspot analysis enabled smarter police patrols and a 50% drop in murders

Internationally, spatial-temporal crime analysis has revealed crime hotspots and temporal patterns that have aided efforts to prevent and reduce crime. This is central to many evidence-based policing practices.

In Trinidad and Tobago, a country with a high level of violent crime, hotspot analysis enabled smarter police patrols and a 50% decrease in murders. The possibilities for data-driven policing (and interventions by those outside the police) to pinpoint and alter violent crime patterns in South Africa are genuine, if not a dire imperative.

In South Africa, access to point-level crime data has been highly restricted in the past, with only a handful of researchers able to use it. A new Institute for Security Studies report on point-level crime data for Khayelitsha is among the first to publish and interrogate such data.

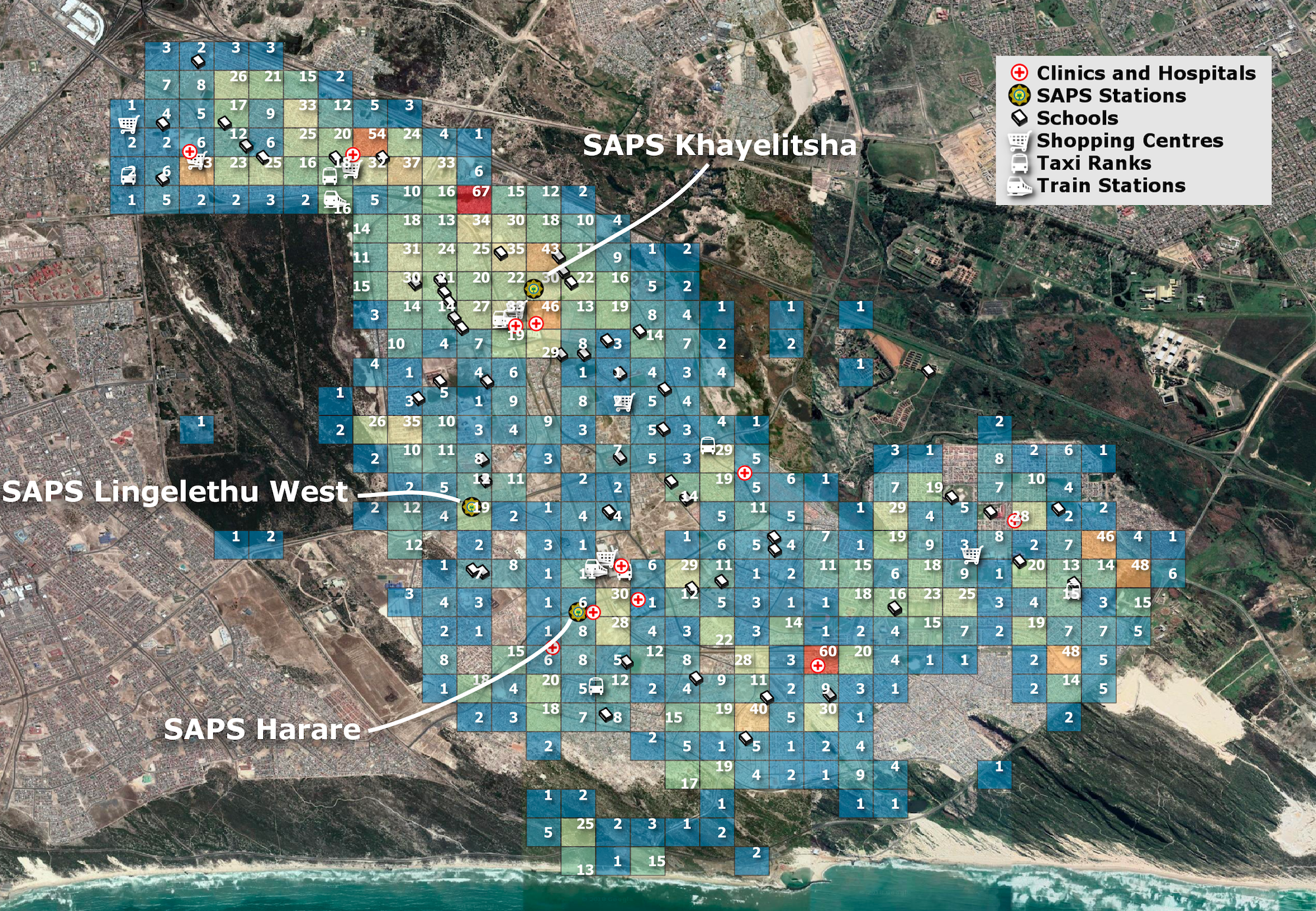

The report shows a general dispersion of crimes across the Greater Khayelitsha area with much higher concentrations near intersections, medical facilities, train stations and even police stations. In the map below, murders in Greater Khayelitsha over the 10-year period are aggregated into 267 m2 blocks, roughly equivalent to a standard city block, and their totals are shown alongside key geographic features. The blocks are colour-coded from blue to red showing increasing murder levels.

Murders in Greater Khayelitsha over 10 years Murders in Greater Khayelitsha over 10 years (click on the map for the full size image) |

Some of these high concentrations may be the result of crimes registered at landmarks rather than their actual locations. All crime records have location data, but in some cases the exact position is unknown (e.g. when a body is delivered to a hospital). If the software used to capture the crime requires a geolocation, input must occur, and landmarks are then used.

This requirement to fill in geolocation data, regardless of its validity, could account for concentrations near medical facilities and police stations. It could also explain the apparent dispersion of unrelated incidents along perfect grid patterns, affecting as much as 10% of all crime data over the 10-year period.

This could result in specific locations being misidentified as crime hotspots and given inappropriate police resource allocations while other actual hotspots (particularly in informal settlement areas where precise geolocation is difficult) may not be identified at all. As a result, SAPS point-level crime data may be too inaccurate and unreliable to be used for hotspot analysis or the development and monitoring of an effective violence prevention strategy.

SAPS point-level crime data may be too inaccurate and unreliable to be used for hotspot analysis

Officially the SAPS says that all stations have functional Crime Information Management and Analysis Centres. These are tasked with combining crime incident records, crime scene investigation evidence, case dockets and offender analysis to enable localised crime mapping on a daily basis.

Unofficially, this is far from reality. Crime locations must be loaded manually into the crime administration system without GPS coordinates taken at the scene nor use of satellite maps for reference. The crime administration system is rarely updated with accurate crime locations. And the incorrect capturing of data means ‘that the planning of crime prevention and interception operations will be inaccurate and futile,’ says former Khayelitsha Cluster Commander Johan Brand (Maj-Gen, retired).

As members of the public, we don’t know how the SAPS makes use of point-level crime data. We also have no insight into how this informs operations in high crime communities, such as those on the Cape Flats, and if police analyses reveal genuine effects from crime prevention or detection initiatives.

Surprisingly, the latest crime statistics reveal that crimes detected as a result of police action have dropped by 22% nationally. This means police are uncovering far fewer crimes during police operations, including illegal firearm possession (down by 10%, despite the increase in murders and use of firearms in 47% of these cases).

South Africa has to build a crime database and test it for itself – this can’t be imported from elsewhere

The 2016 White Paper on Safety and Security calls for a holistic understanding of what drives crime and violence – information that is also needed by other government departments and the public. The policy also requires complete, accurate, readily available and disaggregated crime data. While there are legitimate reasons to protect sensitive data and police intelligence, there is a dire need for evidence-based crime prevention actions involving sectors beyond the police.

South Africa has to build a crime database and test it for itself – this is not something that can be imported from elsewhere. Frequent access to accurate, up-to-date crime data down to point level is a crucial step towards reversing the country’s current crime trends.

Ian Edelstein, independent researcher and ISS consultant

In South Africa, Daily Maverick has exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles. For media based outside South Africa and queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.

Picture: FreddieA/Wikimedia