Africa is losing the battle against extreme poverty

The continent will probably miss the SDG poverty target, but the right policies could deliver significant reductions.

About 30 million more Africans fell into extreme poverty (living on less than US$1.90 a day) when COVID-19 broke out in 2020. Before the pandemic struck, over 445 million people – equivalent to 34% of Africa’s population – lived below the poverty line. Even then, this figure was almost nine times the average for the rest of the world.

In 2015 the United Nations adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as its blueprint for world peace and prosperity. At its core are 17 SDGs with 169 targets for poverty, health, education, inequality, economic growth and climate actions that member countries agreed to achieve by 2030.

As the halfway mark approaches, and with the pandemic worsening the situation, Africa isn’t likely to meet SDG 1 – to end poverty in all its forms for 97% of the population. Africa has the largest share of extreme poverty rates globally, with 23 of the world’s poorest 28 countries at extreme poverty rates above 30%.

Nigeria, Madagascar and Zambia had poverty levels comparable to China, Vietnam and Indonesia in the 1990s

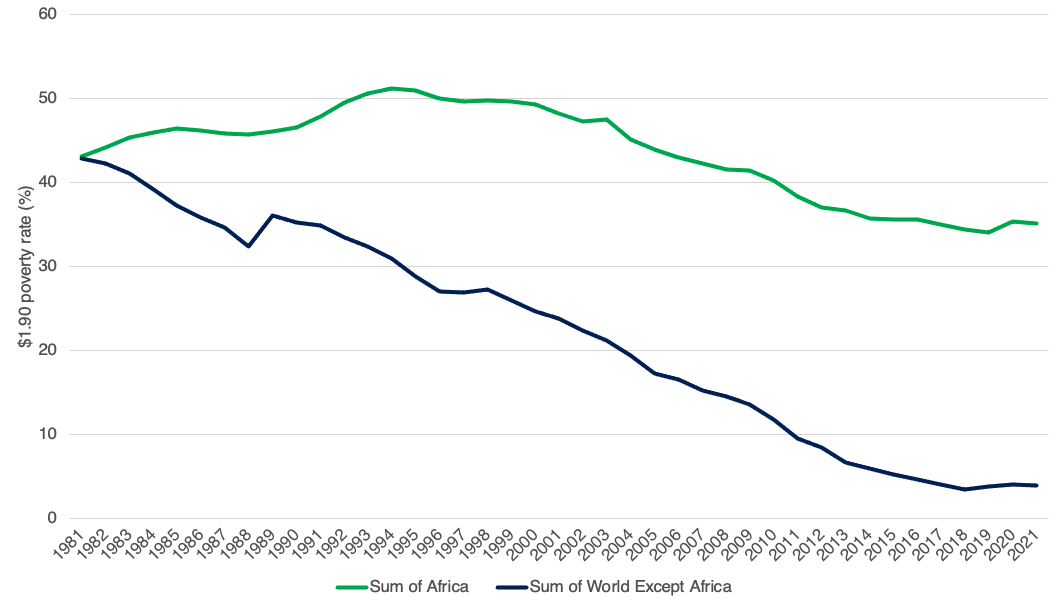

Using the poverty line of US$1.90 a day, Africa’s extreme poverty rate of 43.1% in 1981 was almost equal to the average for the rest of the world’s rate of 42.8%. By 2015 though, Africa’s extreme poverty rate of about 35.5% was 6.8 times the average for the rest of the world (Chart 1).

Chart 1: US$1.90 poverty rate for Africa and the rest of the world, 1981-2021  Source: IFs 7.84 using World Development Indicators data (click on the graph for the full size image)

|

Nigeria, Lesotho, Madagascar and Zambia had poverty levels comparable to China, Vietnam and Indonesia in the 1990s. However, while the last three countries have drastically reduced extreme poverty, African countries haven’t.

Within Africa, most poverty is concentrated in the Sub-Saharan Africa region. Central Africa has the highest extreme poverty rate of 54.8%, followed by Southern Africa at 45.1%. Rates in Western and Eastern Africa are 36.8% and 33.8% respectively. North Africa met the SDG target of a poverty rate below 3% in 2019.

These regional differences mirror the large variance between Africa’s 54 countries. Ten had extreme poverty rates above 50% in 2019. Africa’s poorest country, South Sudan, recorded a rate above 80% and Burundi, Madagascar, the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo all had extreme poverty rates above 70%.

Others have performed well. Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Seychelles and Mauritius had extreme poverty rates below 1% in 2019. Egypt, Cabo Verde and Libya have also met the SDG target.

Africa’s inability to reduce its high extreme poverty rate has been attributed to numerous factors. One is the over-reliance on natural resources for growth instead of agricultural and rural development, which characterises 85% of Africans’ livelihoods. The higher initial poverty levels coupled with low asset ownership and restricted access to public services also make it difficult for households to take advantage of growth. Bad governance, corruption and high-income inequality also drive up poverty.

High fertility rates mean economic growth rates translate into smaller per capita income increases

Africa’s high fertility rates mean that economic growth rates translate into smaller per capita income increases. While the extreme poverty rate will likely fall, the number of poor people will rise due to Africa’s high population growth rate.

By 2030, an estimated 479 million Africans (28.1% of the population) will be living in extreme poverty according to the Current Path – an International Futures (IF) ‘business-as-usual’ scenario used for long-term trend analysis. Central Africa will continue to be the poorest region, with an extreme poverty rate of 44.6% in 2030. North Africa will extend its achievements with an extreme poverty rate of 1.8%.

Although every country’s poverty rate will fall, trends will vary. Nine countries – Egypt, Cabo Verde, Gabon, Tunisia, Seychelles, Mauritius, Algeria, Morocco and Libya – will meet the SDG target by 2030. Conversely, 24 countries will still have more than 30% of their population living in extreme poverty.

By 2043 – when the second 10-year cycle of the African Union’s (AU) Agenda 2063 ends – Africa will still be struggling to meet the 2030 SDGs. By this time, the continent’s extremely poor people will constitute 17.8% of its population. Worryingly, seven African countries will still have extreme poverty rates above 30% by 2043.

An agricultural revolution alone could push 110 million people out of extreme poverty by 2043

Based on Current Path assumptions, Africa will fail to reach the SDG target for extreme poverty, even by 2043. To meet the target by 2030 will require that the rate of poverty reduction quadruples compared to 2013 and 2019, placing the goal out of reach.

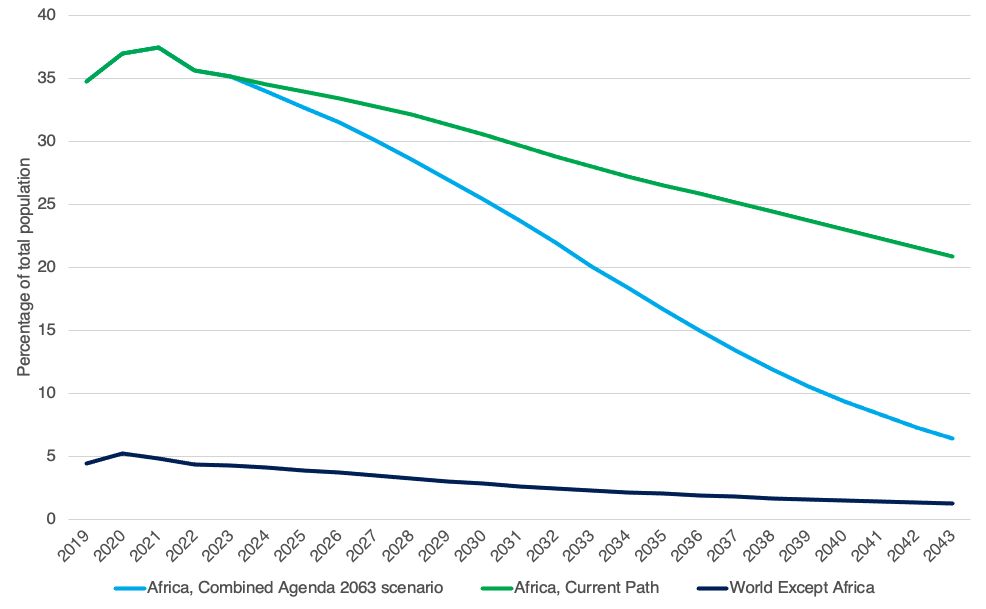

Chart 2: US$1.90 poverty rate for Current Path Africa, the rest of the world, and Africa’s Combined Agenda 2063 scenario, 2019-2043  Source: IFs 7.63 initialising from World Development Indicators data (click on the graph for the full size image)

|

However, with the right policy interventions and political backing, Africa could significantly reduce extreme poverty over the next two decades. An integrated approach is needed that tackles the demographic transition, corruption, bad governance, infrastructure shortage, lack of regional trade integration and poor quality of education. IFs modelling shows that such a combined approach (Combined Agenda 2063 scenario) reduces extreme poverty to 6.4% by 2043 (Chart 2).

Such progress would see 27 African countries eliminate extreme poverty in this period, 17 more than in the Current Path forecast. Indeed, an agricultural revolution alone could push 110 million additional people out of extreme poverty by 2043. Similarly, implementing the African Continental Free Trade Area agreement could account for 80 million more Africans moving out of extreme poverty.

Although eliminating extreme poverty by 2030 is out of reach for most African countries, interventions in key sectors would make a significant difference by 2043. Unless African governments refocus their efforts on implementing the right policies, the continent will likely fail to realise its development potential by the time Agenda 2063 ends.

Enoch Randy Aikins, Researcher and Du Toit McLachlan, Research Officer, African Futures and Innovation, ISS Pretoria

Image: © Amelia Broodryk/ISS

Exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles have been given to Daily Maverick in South Africa and Premium Times in Nigeria. For media based outside South Africa and Nigeria that want to re-publish articles, or for queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.

Development partners

The ISS is grateful for support from the members of the ISS Partnership Forum: the Hanns Seidel Foundation, the European Union, the Open Society Foundations and the governments of Canada, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the USA.